Archaeological fieldwork at Kinloss Abbey

By Dr Steve Worth April 2025

The Cistercian abbey of Kinloss was established in 1150 by David I of Scotland. Kinloss Abbey remained a central focus of monastic life in the northeast of Scotland until the reformation of 1560. Following the Reformation the final abbot, Walter Reid, commenced the selling off its monastic lands and the fabric of the monastery for building material; effectively turning the abbey into a standing quarry. The systematic removal of stone for recycling provided building material for many local civic and agricultural buildings. This continued until the 1840s, when a public outcry was successful in preventing further destruction.

Little remains of this once expansive abbey, only the south transept and the west and south cloister walls remain upstanding. These are situated within the oldest part of the current graveyard, while south of the graveyard are the remains of the Abbot’s house; currently undergoing preservation work by the Kinloss Abbey Trust.

Having lived nearby to Kinloss Abbey for many years and having been a Trustee of the abbey for the past four years, my burning questions about the site are, put simply, just how big was the abbey complex and are there any archaeological remains to be found?

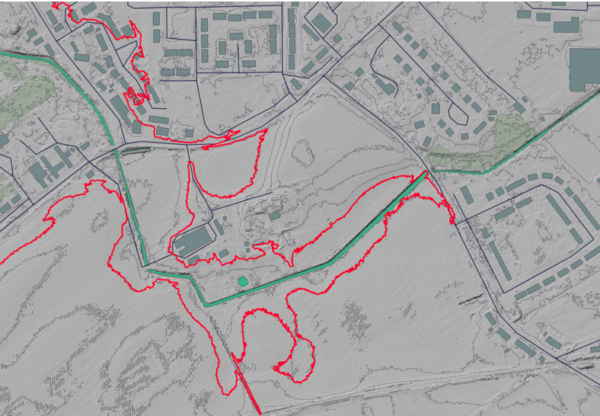

Aerial view of Kinloss Abbey. Google Earth 2025.

The Google Earth image above shows the abbey bounded by the Kinloss Burn to the south and west, this was canalised during the improvements period. Also, the extension to graveyard to the east and the improvement farm buildings to the west would seem to be the obvious areas for the monastic complex. However, Cistercian monasteries of similar scale and importance across the country have far larger footprints than these two areas, and surly the expanded complex couldn’t have been neatly covered by these later additions? Also, the topography of the area would indicate that a likely area for part of the complex would be to the northeast of the graveyard, on the top of the rise. This is clearly seen in a LiDAR image below. The red line shows the 4m contour indicating the obvious promontory of land, a classic example of Cistercian monastic landscapes.

LiDAR image highlighting the 4m contour. Image by M. Sharpe.

To study such a site the question was, literally, where to start. Excavation with the graveyard area was a non-starter. Scheduled monument. And just digging random trenches across the farmers field was again a non-starter. With no previous largescale survey completed this meant a blank canvas lay waiting, and with it the opportunity to discover the scale and layout of the abbey. Therefore, a large scale Geophys study to find an outline of the complex was the order of the day.

I contacted the farmer, Douglas White, who kindly agreed to allow a survey. However, as it was late in the year, with poor weather and the intention to plough in February, meant that this year would initially only be the equivalent of a couple of exploratory trenches.

During previous research I had been lucky enough to come across a survey conducted by William Anderson in 1746 for the Lethen estate, who owned the surrounding land, including Kinloss Abbey, at the time.

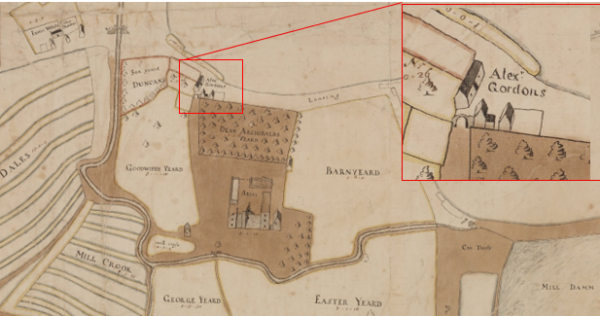

1746 survey by Willaim Anderson of the Lethen estate holdings at Kinloss.

Anderson’s survey provided some opportunity targets. Clearly the overall landscape features remained the same, the road, burn and steadings, but it was the buildings marked ‘Alex’s Gordons’ that drew the eye. Note in the inset an archway over the road leading to the abbey at Alex’ Gordons buildings. Could this be the original gatehouse to the monastery? Also, in the history of the abbey there is mention of a large orchard, could Dean Archibalds Yeard be the remnants of this, and what was the building at its southeast corner?

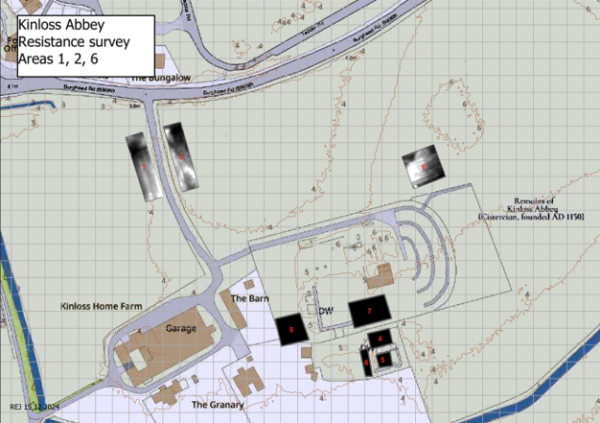

With this in mind I approached the North of Scotland Archaeology Society who kindly lent me their resistivity equipment. I decided to place two 20x40m grids each side of the lane to the abbey (TA1 &TA2) to look for Alex Gordons buildings. Then a 20x 20m grid on the rise to the east to look for the small building at the southeast corner of orchard.

Results from resistivity survey 12th Dec 2024. Image by R. Jones.

Unfortunately, the weather had been poor, both TA1 &TA2 were saturated so the results were at best ‘inconclusive’. TA6, on the higher ground faired much better, but only being a 20x20m grid, although tantalising, was too small to provide a good image. Therefore, we revisited in mid-January. TA1 & 2 remained too wet to survey, TA 6 was extended to a 40m x 40m grid and acting on information from the farmer, who reported large ‘worked stones’ next to the Abbot’s House, TA 9, 20m x 40m, was set up running north-south. Both TA 6 and TA 9 revealed interesting features. We surveyed again in February. At TA2 the ground had dried out, a 40m x 40m grid was surveyed, but remained inconclusive. TA9 was enlarged to a 40m x 40m grid, with results coincident with the report from Douglas White. Also, an exploratory 20m x 20m grid (TA10) was surveyed, again designed to search for the building at the southeast corner of Dean Archibalds Yeard.

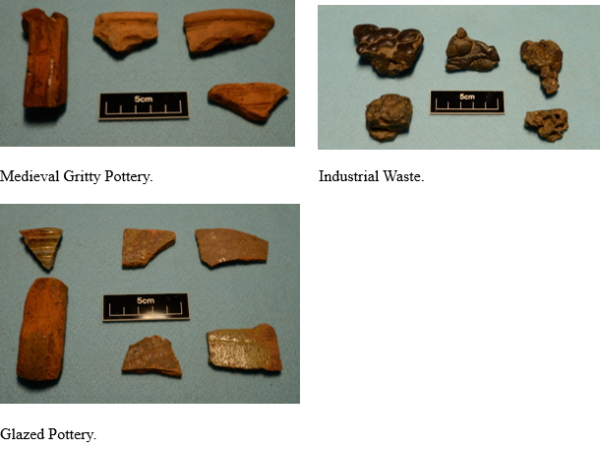

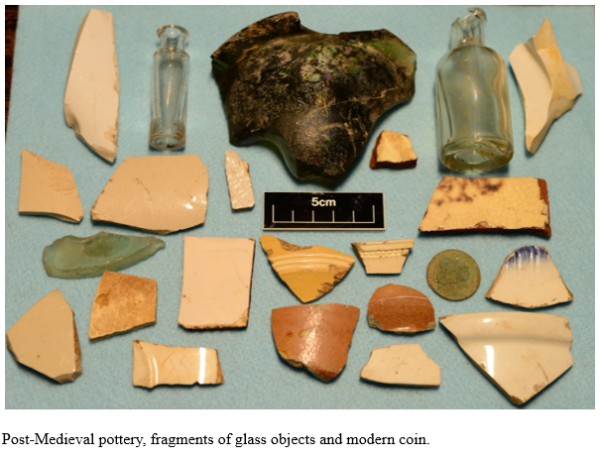

Shortly after this last survey the fields surrounding Kinloss Abbey were ploughed. I took the opportunity to undertake a fieldwalking exercise in March. We concentrated in the field to the west of the access lane, then with what light remained walked the area to the southeast of the graveyard.

The area to the west had a large concentration of mixed finds, from flints, industrial waste, glass and medieval ceramics plus an assortment of post medieval artefacts, see below. Of specific interest was the glazed and medieval pottery fragments, certainly dating from the monastic period.

These field exercises are the first stages in a far wider study of the abbey. It is intended to conduct a full resistivity survey around the graveyard out to 40m after harvest. This, it is hoped, could identify areas of the monastic complex for further investigation. Also, a second fieldwalking exercise will add to the data already collected.

Fieldwork at Kinloss Abbey has the potential to uncover the unrecorded story of the abbey, showing the true impact on the landscape of this once imposing structure. With the support of Douglas White, NOSAS and friends the next campaign should hopefully see a major step forward in this research.